For more information or if you need help retrieving your data, please contact Weights & Biases Customer Support at support@wandb.com

AI agents are rapidly moving into real-world use. A 2024 McKinsey report finds that 65% of businesses now use generative AI in at least one function, suggesting enterprises are increasingly open to automating tasks that previously required human effort. With this shift comes a critical challenge:

How do we evaluate what these agents are doing, not just in terms of technical accuracy, but also independence, safety, and real business value?

Agent evaluation is the process of measuring how well an AI agent performs across three dimensions: technical ability, autonomy, and business impact. It’s not just about what the agent can do (such as calling APIs, using tools, or routing tasks), but also about how independently it operates and whether it can be trusted to stay within its boundaries. An agent with access to system operations isn’t just another software feature. Without proper evaluation, it can make decisions you didn’t intend, trigger actions in the wrong context, or escalate harmless tasks into real problems. That’s why understanding its behavior isn’t optional; it’s the only way to prevent subtle mistakes from turning into expensive or unsafe outcomes.

This article breaks down the two frameworks that matter:

Together, they shape how we measure success. Engineers care about performance and latency; risk teams want

agentic guardrails; and executives want clear evidence that AI-driven automation delivers real, defensible ROI. Evaluating agents properly means balancing all those needs at once.

The goal here is simple: equip you with a practical framework to evaluate an agent’s output and behavior, ensuring it’s not just functional, but safe and aligned with your business goals.

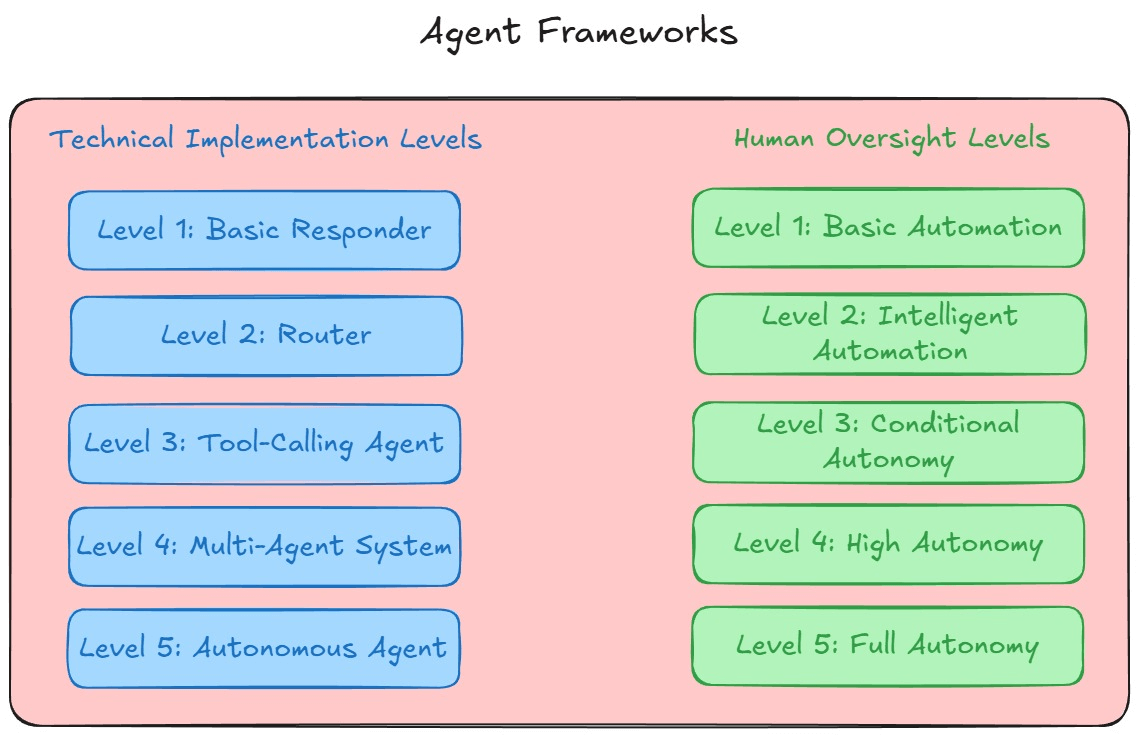

Understanding AI agents starts with two foundational frameworks:

These frameworks describe two different qualities of an agent: what it’s capable of doing, and how independently it’s allowed to operate. You need both to understand how an agent behaves in practice.

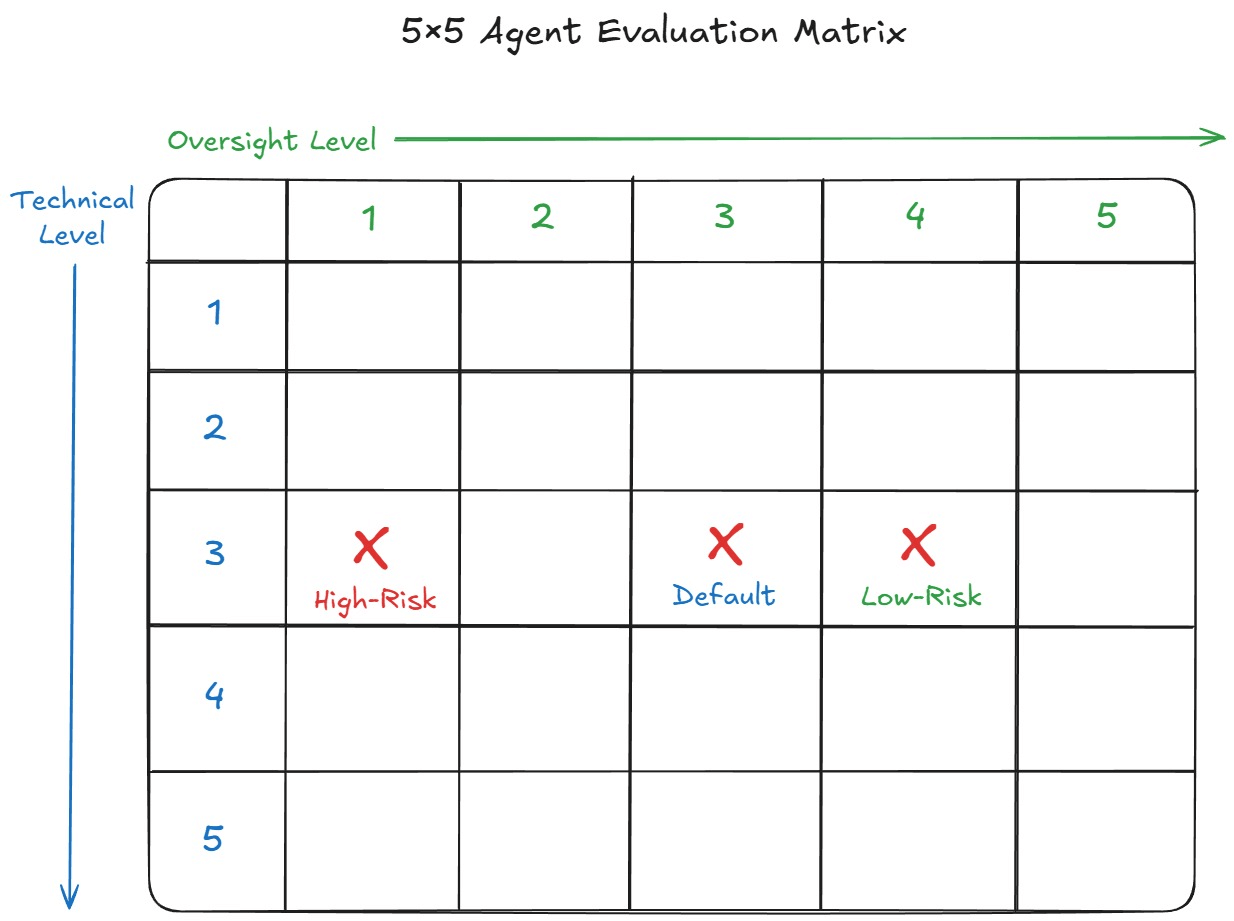

These two scales don’t always move together. A Level 3 tool-calling agent might operate under strict supervision in a financial setting but run with minimal oversight in low-risk environments. A simple 5×5 matrix helps visualize this separation and reminds us that technical complexity does not automatically imply high autonomy.

As shown in the matrix above, a Level 3 tool-calling agent can be assigned to Oversight Levels 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5, depending on risk, not capability.

Evaluating an autonomous AI agent means looking beyond whether it “works” in a single moment. A strong agent evaluation framework should reveal what the agent can do, how independently it should operate, and whether humans can trust its behavior in real conditions. It’s similar to evaluating a pilot rather than just a plane. You assess skills, decision-making, and judgment under pressure.

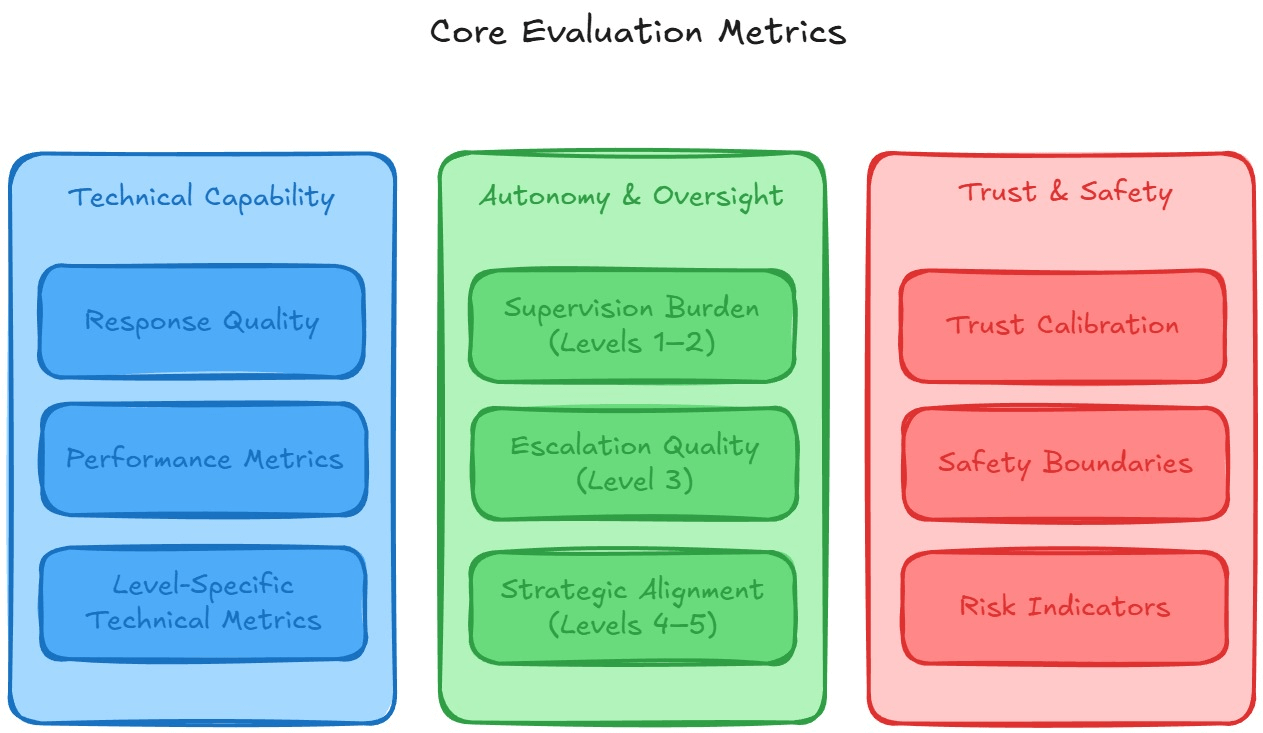

This section breaks those ideas into three practical dimensions:

Together, they give you a complete picture of how an autonomous agent behaves today and how reliably it will perform as responsibilities and risk increase.

Technical capability metrics measure the agent’s raw performance; the quality of its outputs, the speed of its responses, and how efficiently it uses system resources.

Autonomy and oversight metrics focus on the extent of human supervision required and on whether the agent correctly escalates or defers decisions.

Trust and safety metrics ensure an agent behaves reliably and transparently, especially in ambiguous or high-risk situations.

Different types of AI agents require distinct evaluation strategies because each level introduces new capabilities, risks, and failure modes. Evaluating them is a bit like evaluating vehicles on a road: you wouldn’t apply the same safety checklist to a bicycle, a car, and a self-driving truck. As agents gain more autonomy and access to tools, the questions you ask and the metrics that matter change significantly.

This section walks through each level individually, outlining what to measure, the appropriate level of independence, where things commonly break, and which executive-level metric signals real value at that stage.

What to measure

Autonomy considerations

Key failure modes: Hallucinations, repetitive loops, and vulnerability to prompt injection.

Executive metric: Customer satisfaction score and overall cost per interaction.

What to measure

Autonomy considerations

Key failure modes: Intent misclassification and over-confident routing.

Executive metric: First-contact resolution rate.

What to measure

Autonomy considerations

Key failure modes: Incorrect tool selection, parameter hallucination, and cascading failures from repeated tool misfires.

Executive metric: Task completion rate and measurable automation ROI.

What to measure

Autonomy considerations

Key failure modes: Deadlocks, excessive communication overhead, and diffusion of responsibility.

Executive metric: End-to-end process efficiency.

What to measure

Autonomy considerations

Key failure modes: Goal misalignment, value drift, and overconfidence in unfamiliar domains.

Executive metric: Human intervention hours saved.

| Agent Level | What to Measure | Autonomy Range | Common Failure Modes | Executive Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 — Basic Responder | Relevance, factual accuracy, latency, token efficiency | Intelligent Automation | Hallucination, repetition loops, prompt injection | Customer satisfaction, cost per interaction |

| Level 2 — Router | Precision/recall/F1, confusion matrix, multi-intent detection, fallback handling | Conditional Autonomy | Intent misclassification, over-confident routing | First-contact resolution rate |

| Level 3 — Tool-Calling Agent | Tool selection accuracy, parameter extraction, error recovery, cost optimization | Conditional → High Autonomy | Wrong tool selection, parameter hallucination, cascading failures | Task completion rate, automation ROI |

| Level 4 — Multi-Agent System | Orchestration efficiency, handoff success, system-level goal completion, credit assignment | High Autonomy | Deadlocks, communication overhead, diffusion of responsibility | End-to-end process efficiency |

| Level 5 — Autonomous Agent | Independent goal achievement, cross-domain generalization, adaptation rate, novel solutions | Full Autonomy (theoretical/high-risk) | Goal misalignment, value drift, overconfidence | Human intervention hours saved |

Evaluating an AI agent requires examining both the system in operation and the individual components that power it. These two perspectives serve different purposes: end-to-end testing shows whether the agentic system delivers real value, while component-level testing explains why something works or fails.

Using both approaches together gives teams a comprehensive understanding of performance, reliability, and opportunities for improvement.

End-to-End Evaluation (E2E)

Use this when the goal is to validate:

E2E answers the big question: Does the system work as a whole?

Use this for optimization, debugging, and diagnosing bottlenecks. Examples:

Component testing answers: Where exactly is performance breaking down?

Some issues only appear when components interact. Integration tests help detect:

A practical rule of thumb is 70% end-to-end testing (for production confidence) and 30% component-level testing (for optimization and reliability). This balance keeps the system user-ready while leaving room for targeted improvements.

| Aspect | End-to-End Evaluation | Component-Level Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Validate overall system performance and business value | Diagnose and optimize individual components |

| Focus Area | Full workflow from input to final output | LLM, retriever, tool-caller, orchestrator, etc. |

| Best For | User experience, compliance, reliability | Debugging, accuracy improvements, performance tuning |

| Scope | Broad, holistic view of the system | Narrow, deep investigation of one subsystem |

| Failure Detection | Detects user-visible or system-wide failures | Identifies root causes and bottlenecks |

| Cost & Time | More expensive and slower to run | Faster iterations with lower cost |

| When to Use | Before release, during production monitoring | During development, troubleshooting, optimization |

| Output Quality Signals | Task success rate, latency, user satisfaction | Precision@k, F1 score, error-handling quality |

| Risk Indicators | Workflow-level breakage, compliance gaps | Misrouting, tool-call errors, retrieval drift |

| Recommended Share | ~70% of total evaluation effort | ~30% of total evaluation effort |

A reliable evaluation framework depends on a well-designed test suite. The goal isn’t just to check whether an agent works once, but to consistently validate its behavior across typical scenarios, unusual situations, and recurring issues. A strong test suite ensures agents remain stable as they evolve, scale, and interact with more complex environments.

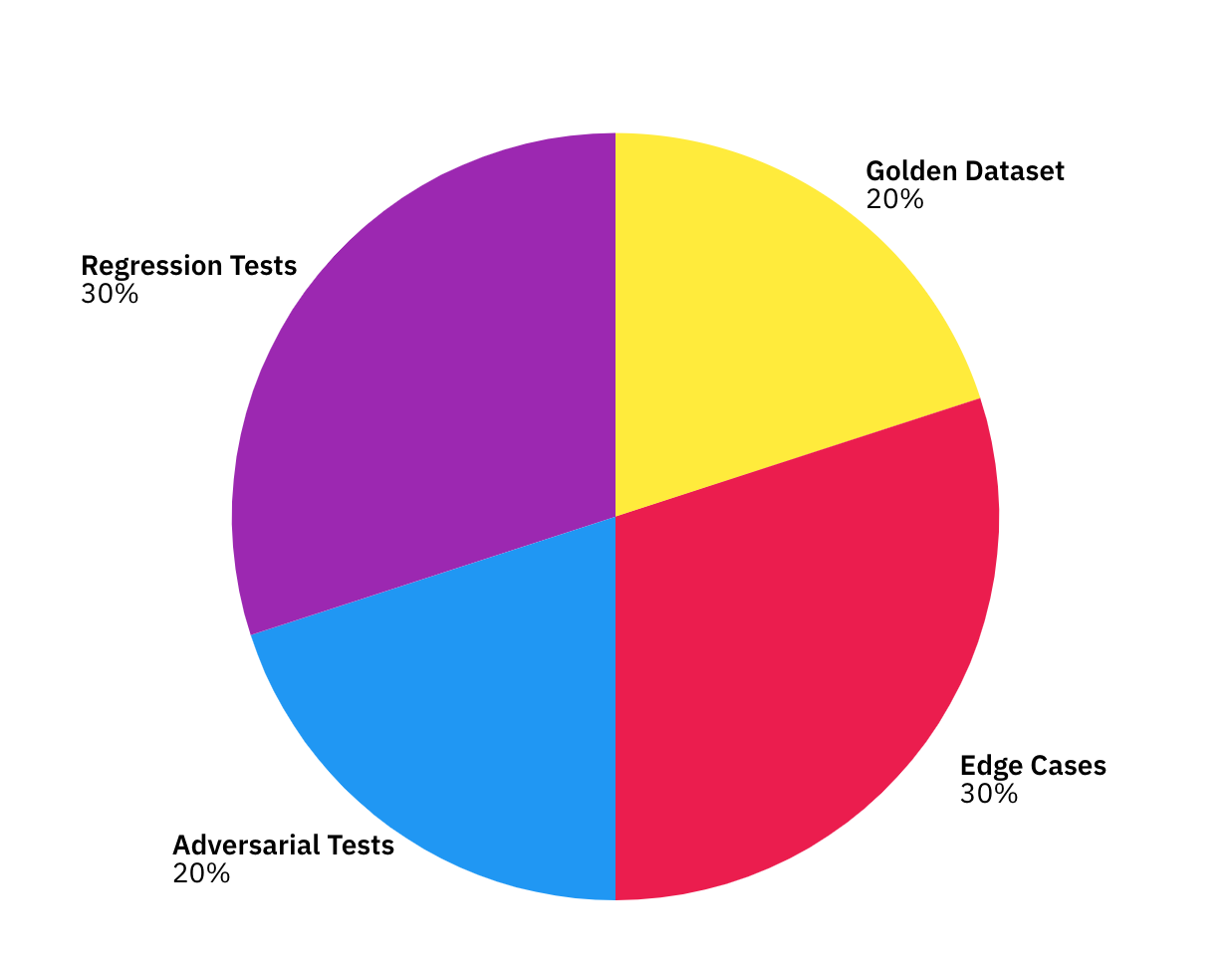

A balanced test suite should include four key categories:

Not all tests carry the same weight. A simple scoring model helps focus on what matters:

Score = Business Impact × Frequency × Autonomy Risk

High-priority tests typically involve high-frequency tasks performed by highly autonomous agents, especially where errors affect customers or compliance. Test priorities should be updated regularly based on production failures.

Synthetic data is especially valuable when real inputs can’t be used due to privacy restrictions or when certain scenarios don’t occur often enough to test reliably.

For example, a banking agent might rarely encounter a fraudulent transfer request, yet it still needs to respond correctly every time. Synthetic versions of these rare events let you expand edge-case coverage, simulate high-risk scenarios safely, and run large-scale stress tests without exposing any sensitive customer information.

Test suites must grow with the system. This includes version-controlling test files, retiring outdated scenarios, and continuously adding new cases discovered during real-world operation.

Even well-designed agentic systems fail, and while the failures may not be predictable, they often follow recognizable patterns that emerge over time. Understanding these patterns matters because debugging agents isn’t like debugging traditional software. You’re not fixing a broken “if-else” statement; you’re diagnosing a system that reasons, adapts, and collaborates.

Think of it like diagnosing a city’s traffic jam: you’re not looking for a single broken light, but the chain of events that caused the entire flow to stall. Recognizing these patterns early makes your systems more stable, easier to scale, and safer to deploy.

Different agent levels introduce different technical weaknesses:

Technical accuracy isn’t enough; autonomy introduces its own risks:

A simple but powerful workflow:

Trace analysis → Root cause identification → Pattern recognition → Preventive measures

Think of it like replaying the “flight recorder” of an agent’s reasoning: where did it drift, who handed off what, and what triggered the break?

To reduce recurring failures, teams rely on:

Once an autonomous AI agent is deployed, evaluation becomes an ongoing responsibility rather than a one-time checklist. Production monitoring matters because AI systems don’t fail loudly; they drift. Performance can decline slowly, behavior can subtly change, and autonomy can introduce new risks as agents adapt to real-world data.

Think of this phase as monitoring a self-driving car: even if it passed every test in the lab, you still need real-time sensors, alerts, and course-correction while it operates on real roads.

These metrics track how the system behaves moment by moment:

Agents naturally face “drift,” where their performance shifts over time. Watch for:

Ignoring drift is one of the fastest ways to lose reliability at scale.

Alert sensitivity should match autonomy:

Healthy production systems learn continuously:

These loops ensure the agent gets safer, more accurate, and more aligned over time — not just more active.

Even the best evaluation framework is useless without the right tools to support it. Production agents generate thousands of interactions, logs, tool calls, and reasoning traces. Without proper observability and testing infrastructure, teams end up “flying blind,” unsure why an agent succeeded, failed, or changed its behavior. This section outlines the key tool categories you’ll need and how to roll them out in a practical, phased timeline.

1. Observability platforms

These track system-level performance and infrastructure metrics.

2. LLM/Agent-specific tools

These capture model calls, tool invocations, and agent decision traces, with support for visualizing how the agent arrived at an output.

3. Automated testing frameworks

These run test suites continuously against your agents.

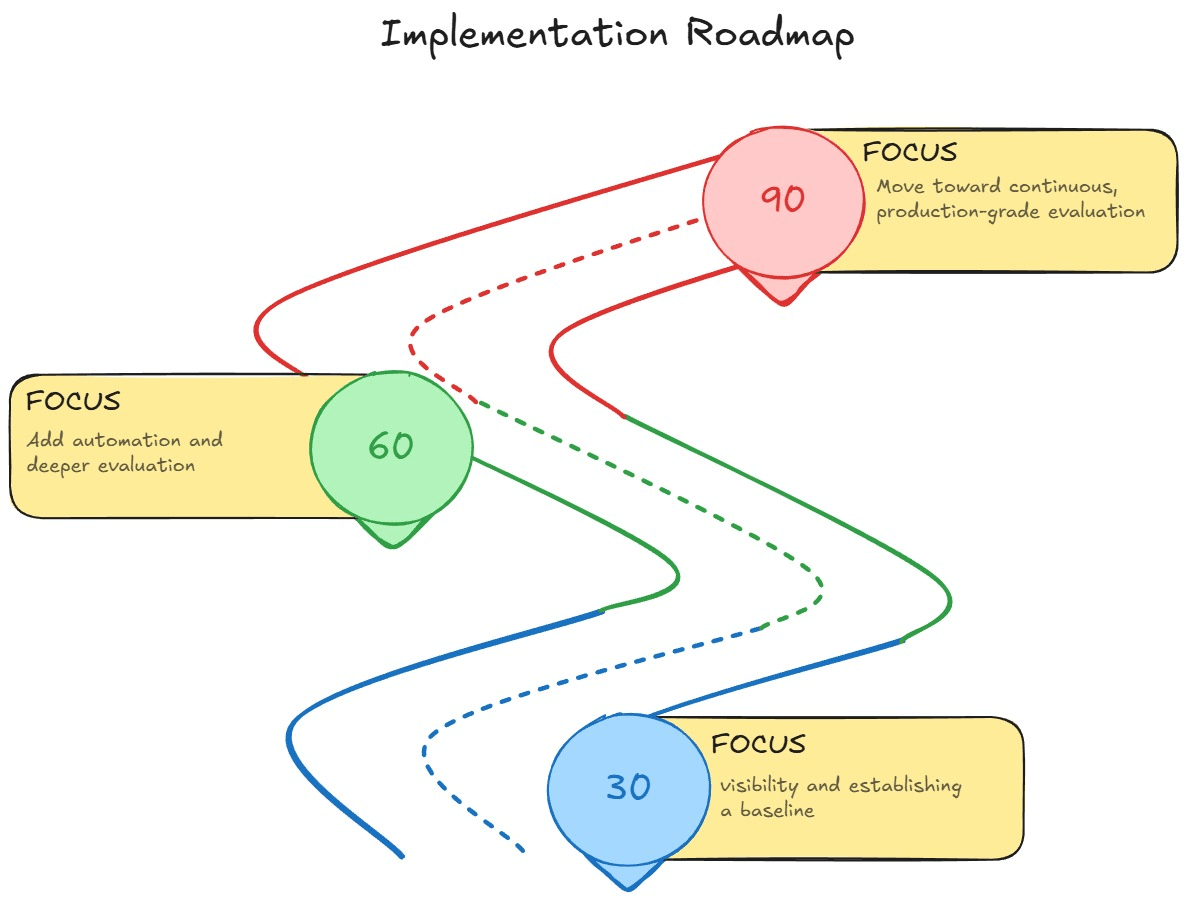

A practical rollout timeline:

A reasonable rule of thumb: 1 engineer per 2 agents for setup, and 0.5 engineer for ongoing maintenance as the system scales.

Deploying AI agents isn’t just a technical decision; it’s a financial and operational bet. Organizations need to understand whether an agent actually delivers measurable value and how much risk it introduces as autonomy increases.

Think of this as evaluating a new employee: you measure their output, the cost of supporting them, and the risks they take on. Without this lens, it’s easy to overestimate benefits or underestimate governance needs.

A practical ROI model focuses on comparing what the agent saves versus what it costs:

ROI Formula:

$$ROI = \frac{\text{Benefits} – \text{Costs}}{\text{Costs}} \times 100\%$$

Example: If an agent saves $50k but costs $25k to operate, the ROI is 100%.

Risk grows with autonomy because the agent takes more independent actions:

Different teams evaluate agent value through different lenses:

Higher autonomy costs more to implement but yields greater long-term leverage when implemented safely. The goal is to find the level where benefits clearly outweigh operational and risk overhead.

Implementing an evaluation system for AI agents is not something teams can do overnight. It requires layering the right foundations in the right order so the system stays reliable as autonomy increases.

Think of this roadmap like building a house: you start with plumbing and wiring (logging), then walls (testing), and only later add the smart-home automation (continuous evaluation).

Moving too fast risks instability; moving too slow limits value. This phased approach ensures agents grow safely and predictably.

Focus on getting visibility and establishing a baseline.

This phase provides teams with an “early warning system.”

Add automation and deeper evaluation.

This phase transitions the team from manual review to structured, reliable validation.

Move toward continuous, production-grade evaluation.

By this stage, the system becomes self-improving rather than reactive.

This ensures scale doesn’t outpace safety or reliability.

Autonomous agent evaluation will evolve as quickly as the agents themselves. As autonomy grows, traditional testing won’t be enough to keep systems safe, aligned, and effective. The shift is akin to moving from evaluating a calculator to evaluating a junior analyst who learns, adapts, and makes independent decisions.

Regulations will introduce clearer standards, certifications, and transparency expectations, especially for high-risk agents. As systems move toward broader problem-solving capabilities, evaluation must expand beyond task accuracy to include reasoning quality, adaptability, and long-term goal alignment.

For organizations, human roles will shift from operators to strategic overseers who design frameworks for safety and value. The most successful teams will start simple, build evaluation habits early, and treat assessment as an ongoing discipline rather than an afterthought.